Over the past twenty years or so, I must’ve put in thousands of hours into more than two hundred video games. Now, if you gave me ten seconds to list as many of those games as possible, here’s what you’d get:

World of Warcraft

Final Fantasy series

Pokemon series

The Witcher series

Assassin’s Creed series

Red Dead Redemption

Flappy Bird??

With the exception of Flappy Bird (I panicked at around second nine), you’ll notice that most of these games belong to the broader roleplaying genre. But they have something else in common: All of these RPGs consisted of extensive game worlds that kept me invested for weeks—sometimes even months, and in the case of World of Warcraft, years.

Their lore was expanded with sequels and prequels, expansions, exclusive DLCs, special in-game events, and so on.

This got me thinking: How exactly do these extraordinary settings draw players into the game? We asked some of our friends in game development to help us shed some light on the complex art of worldbuilding.

They’re Inhabited by Unique Characters

When creating worlds, most creators start with the protagonists of the story. Who are they? What do they want to achieve, and how will they do it? Single-player experiences require characters whose aspirations push the story forwards.

These characters need their own distinct personality, design, backstory, and voiceover. Well-made video game characters have the potential to become icons and spawn gigantic franchises (e.g., Mario, Link, Crash Bandicoot, Lara Croft, Master Chief, Kratos).

Studio Evil’s Super Cane Magic ZERO

They’re Detailed, Memorable, and Consistent

Once the main characters begin to take shape, the creation of the game’s world becomes a top priority.

A game world creates the context for the stories of your characters. Sometimes I like to think of my world like an extra character of the story, and I try to intertwine its own evolution arc with the characters' one.

–Marco Di Timoteo, Creative Director at Studio Evil

Great game worlds are believable, even if the story takes place in a distant galaxy some thousands of years in the future. The narrative needs to be consistent, and the world must reflect that narrative with small details that bring everything together. Think of architecture, clothing, prop placement, and language in the Assassin’s Creed series: they’re always fleshed out and true (as they can be) to the time the story’s based on.

Acorn’s Social Media Strategist, George Eastmead was fortunate enough to meet producer of the Assassin’s Creed (2016) movie, Frank Marshall in a preview event for the movie the year prior. In conversation, Marshall explained how the Assassins series spanned so many periods of history, but each was immediately recognisable on account of the character design and environment. He later explained how it was vitally important that the upcoming movie followed this trend, especially with scenes set across multiple timescapes.

How’s It Done?

Eelements that promote immersion by bringing worlds to life include:

History

Politics

Ethnography

Religion and beliefs systems

Wealth and currency details

Everyday life and habits

Information about the universe’s flora and fauna

This list isn’t exhaustive. Worlds can set their own rules, but they need to respect those rules. Think how the Force works in the Star Wars universe or how Superman grows weak when he comes in contact with Kryptonite. Rules and general world balance create points of reference that make a story believable.

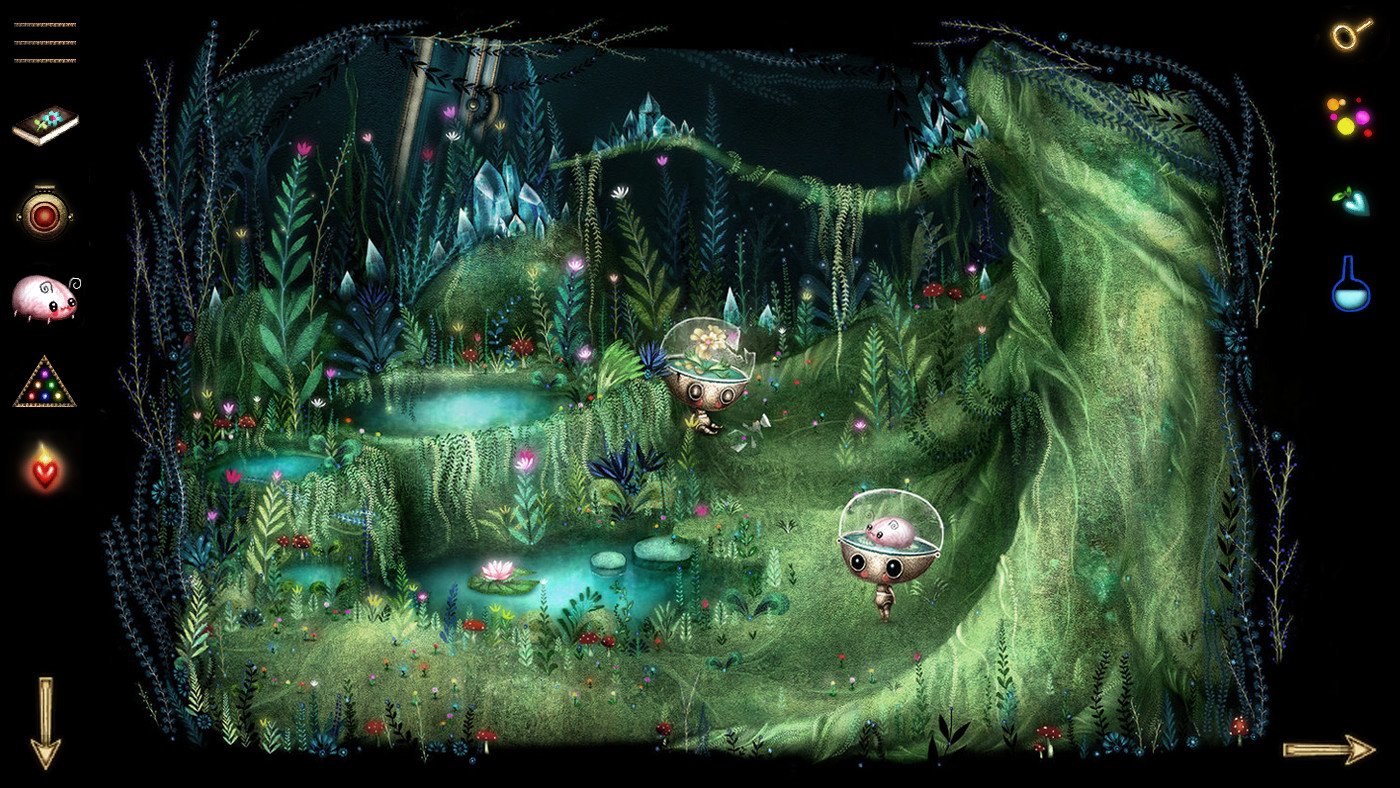

Wabisabi Play’s Growbot

You can take advantage of your environment and protagonists’ actions to bring many of these elements to the forefront. Growbot, for example, uses clever environment design to help players better understand how the game world works:

The biopunk machinery and circumstance hopefully create intrigue about how the world works and the nature of the creatures who reside there.

–Lisa Evans, Wabisabi Play

You need to be careful not to break immersion by adding objects and elements that don’t fit the referenced era (e.g., a random electronic sound effect in a medieval fantasy world).

That said, adding too many details—especially at the beginning of development—isn’t always a good idea:

“My biggest challenge is finding the right balance in worldbuilding so that I have a world that is detailed enough to help me make a better game, but not too much that is actually slowing me down because I have to keep everything coherent every time I decide to change a tiny bit of the whole structure.”

–Marco Di Timoteo, Creative Director at Studio Evil

They’re Relatable

Great game worlds might be fictional, but they’re always tied to relatable human emotions and experiences—even when the protagonists themselves aren’t human. Like writers and filmmakers, game developers are tasked with moving and inspiring their audience—which is especially difficult when the story isn’t set in the real world. Connecting with realistic and grounded characters adds perspective to even the strangest of fantasy landscapes.

Lantern Studio’s LUNA The Shadow Dust

The game world can be really different from ours, but it needs to, at some level, reflect our reality. It can go against our common sense to play as a surprise factor, make things feel exotic, or it can be similar to our world so that we can fully immerse ourselves in the environment and get on with the adventure.

—Beidi Guo, Lantern Studio

The setting might be all made up, but if creators want players to care, the game world must act as a channel for interactions that evoke real and honest human emotions. Growbot makes you care about sentient robots aboard a space station full of plants, flowers, and biopunk machinery by telling a human story of betrayal and duplicity against its backdrop.

They Provide Storytelling Opportunities

Another characteristic of well-designed worlds is that they don’t feel forced or rushed. If the goal is to allow players to connect with their game, developers need to find ways to create not just a generic fantasy setting but a storytelling medium.

Ideally, game worlds should help you tell your story through well-placed clues and meaningful interactions with important game characters.

The world should reflect the story, and the story should respect the world. When done right, the setting itself can help players make sense of things without the need for dialogue, cutscenes, and boring text explanations. Such is the case with LUNA The Shadow Dust:

“Since our game doesn't have any word or dialogue, the environment (visual and music) played a big part in storytelling. We designed a lot of places (e.g., library, gallery, great hall) which allows wall paintings and books to tell the lore of the world in a visual way.”

–Beidi Guo, Lantern Studio

The otherworldly setting of Growbot, too, comes to life with fantastic plants and aliens that the player can interact with. The game’s music score reflects this magical yet bizarre experience, and you even get the chance to collect the sounds of flowers (which you can use to defend yourself).

Why Does Worldbuilding Matter?

“Worldbuilding creates a space for possibility and excitement.”

–Lisa Evans, Wabisabi Play

Even when you’re not building a vast open-world sandbox game, it matters. Well-thought-out and carefully-designed settings make things exciting and breathe new life into tired tropes. You need to give players a chance to connect with your characters and immerse in the environment by alluding to a world that transcends the story itself (i.e., it isn’t immediately obvious it exists only for your story’s sake):

“Especially when we talk about games, you have to give players the impression that there is more to discover inside the game. A game world is like a structure for you to build upon and for the players to explore.”

–Marco Di Timoteo, Creative Director at Studio Evil

This desire for exploration might explain my obsession with fantasy role-playing games. When everything goes right, they feel real and alive but also boundless and expansive.

Sandbox games, such as Far Cry, take this principle one step further, presenting a life-like environment where things happen (e.g., random events, NPC conflicts) even when the player isn’t actively involved.

Massive Online Worlds

Rather than relying on personal story development, MMORPGs come to life by placing thousands of players into a shared game world. They rarely limit players to one specific gameplay style, and I love how I can advance through the story while also getting pleasantly sidetracked from time to time (e.g., by exploring new regions, learning new skills, mastering a new craft).

MMOs are often more static than most single-player sandboxes, but they truly shine when they adopt dynamic elements. With cascading events, environment changes, and multiple outcomes, Guild Wars 2 is an excellent example of an MMO that does dynamic gameplay justice.

I will never forget “The Shattering”, the World of Warcraft event that hit the live servers a few weeks before the official release of Cataclysm in 2010. Big scary dragon, Deathwing swept through Azeroth, spitting vengeful fire, forever changing many of the game’s beloved regions. Players could see Deathwing fly above in real-time, bringing death and destruction in his wake. Seeing everything engulfed in flames made sense, and it was an excellent introduction to the game’s third expansion.

This kind of huge environment-changing ‘event’ has made its way to other online games in recent years, with competitive multiplayer titles like Fortnite and Call of Duty: Warzone now exhibiting them in many of their battle arena modes, forever changing familiar digital landscapes that players return to on a daily basis.

Fundamentally, environmental design plays an important role in telling the story, establishing the parameters of gameplay and creating lasting memories for players. Where would we be without some of the incredible worlds listed at the start of this article. What is your favourite fictional world?